What is church polity? A Guide to Governance Models

- The Bible Seminary

- Dec 1, 2025

- 16 min read

When you hear the term church polity, your eyes might glaze over. It sounds like one of those dry, seminary-classroom words that has little to do with actual ministry. But stick with me here, because nothing could be further from the truth.

Think of it this way: church polity is simply the framework a church uses to govern itself. It's the operating system, the organizational blueprint that answers all the practical "how-to" questions. How do we hire a pastor? Who owns the church property? How are major decisions made? That's all polity.

Understanding Church Governance

Let’s try an analogy. If a church’s theology and mission are its heart and soul, then its polity is the nervous system. It's the structure that connects everything and coordinates every action, from the smallest committee meeting to the biggest doctrinal decision. It’s how a church answers foundational questions about authority and order.

Without a clear polity, a church would stumble through its most basic operations. Who has the final say on the budget? How do you call a new pastor? Who is responsible for church discipline? Church polity provides the road map for navigating these crucial functions, giving the ministry clarity and purpose to move forward.

The Three Main Blueprints

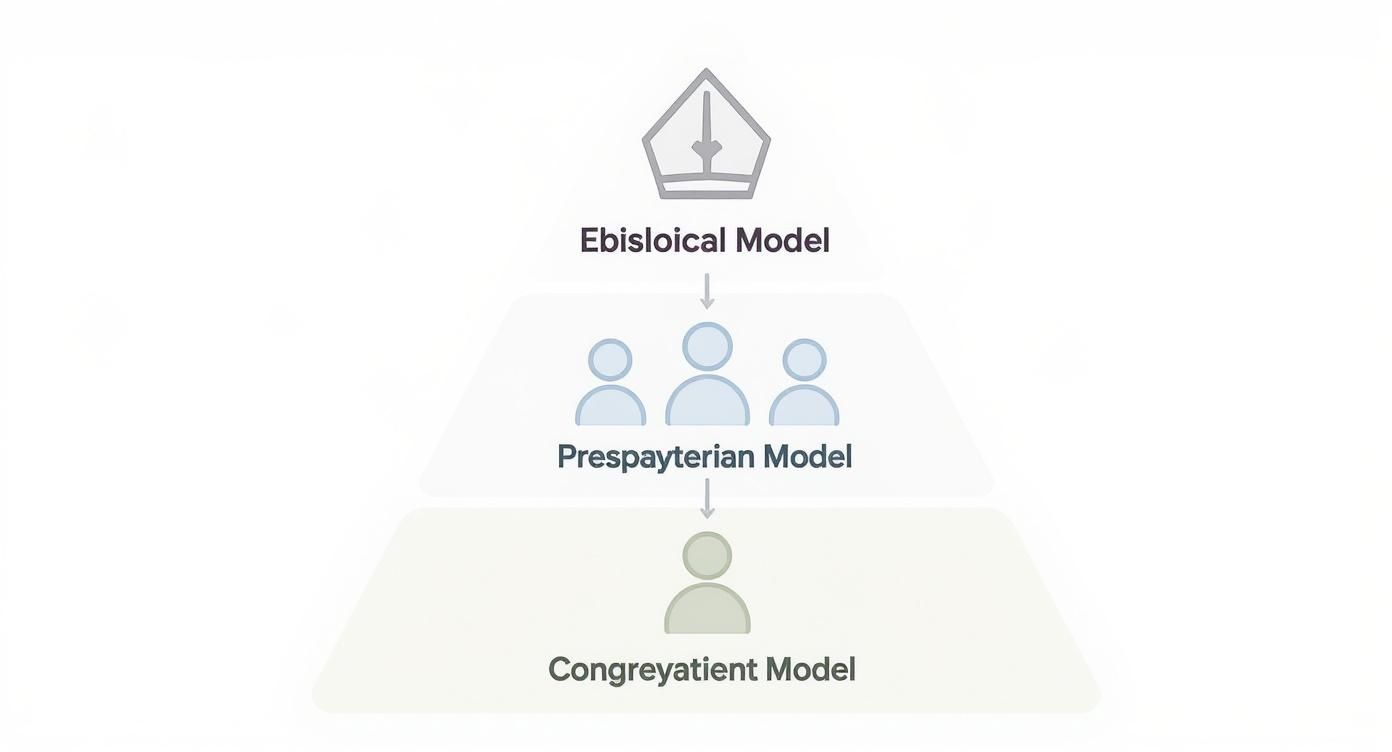

While you’ll find plenty of local variations, almost every Christian church operates on one of three foundational models of governance. Each one has a different answer to the question, "Where does the buck stop?"

Episcopal: This is a hierarchical model where authority flows downward from bishops to local priests or pastors. You can think of it like a corporate structure with clear, top-down leadership.

Presbyterian: This is a representative model. Authority rests with a group of elected elders (presbyters) who govern through councils at the local, regional, and even national levels. It’s structured much like a republic.

Congregational: This model champions the autonomy of the local church. Here, the final governing authority rests with the members of the congregation itself. It essentially operates as a direct democracy.

More Than Just a Technical Term

Grasping what is church polity is absolutely critical because it shapes the entire culture, ministry, and day-to-day life of a church. For pastors, the governing structure defines their autonomy, their accountability, and the processes they have to follow. For members, it clarifies their role in decision-making and how they connect to a larger denomination, if there is one.

In short, when image is everything, the cross is eclipsed. A healthy polity is designed to keep leadership and laypeople alike accountable, preventing a focus on public image from overshadowing the core mission of humility and transparency.

The leadership structure is often visualized to make roles and responsibilities crystal clear. If you're looking for practical examples of how these models are laid out, exploring guides on creating effective church organizational charts can be incredibly helpful.

Ultimately, polity is where theology gets practical. It’s the outworking of a church’s convictions about leadership, community, and authority. It is far more than an administrative detail; it’s the very system that empowers a church to faithfully live out its calling.

Exploring The Three Major Church Governance Models

Now that we have a handle on church polity as the "operating system" for church governance, we can dive into the three major models that have historically shaped Christian communities. Each one gives a different answer to the big question: Where does authority rest, and how are decisions made? You can think of them as three distinct blueprints for building and leading a church.

To get a better picture, imagine three different ways of governing a country. One might be a constitutional monarchy with a clear head of state (that’s like the Episcopal model). Another could be a representative republic where elected officials make decisions for the people (think Presbyterian). And a third might look like a local town hall meeting where every citizen gets a direct vote on key issues (that's the Congregational model). Each structure has its own flow of power and real-world implications.

The Episcopal Model: A Hierarchy of Authority

The Episcopal model is, at its heart, a hierarchical system. The name itself comes from the Greek word episkopos, which means "overseer" and is often translated as "bishop." In this structure, authority flows from the top down.

At the highest level, bishops hold spiritual and administrative authority over a geographic region called a diocese. These bishops are tasked with ordaining and appointing local clergy—priests or pastors—to individual churches. They also provide doctrinal oversight, ensuring the churches under their care stick to the broader traditions and laws of the denomination.

This top-down structure creates a high degree of organizational unity and doctrinal consistency. With clear lines of authority, decisions can be made and rolled out efficiently across a wide network of churches. You'll see this model in denominations like the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, and Methodist churches. The global Catholic Church is a massive example, with its roughly 1.406 billion members worldwide governed by a centralized hierarchy led by the Pope.

The Presbyterian Model: Representative Governance

The Presbyterian model, on the other hand, works a lot like a representative republic. Its name is derived from the Greek word presbuteros, meaning "elder." In this system, authority isn't concentrated in a single individual like a bishop but is held by a group of elders elected by the congregation.

These elders form a local church council, often called a session or consistory, which governs the affairs of that specific congregation. But the authority doesn't stop at the local level. This model connects churches through a series of higher governing bodies.

Presbytery: A regional body made up of ministers and elder representatives from each local church in that district.

Synod: A larger governing body that oversees multiple presbyteries within a broader geographical area.

General Assembly: The highest national court of the church, composed of representatives from all presbyteries, which makes final decisions on doctrine and discipline.

This layered structure builds in both local representation and mutual accountability. Local churches have a voice in the wider denomination through their elected elders, but they are also held accountable to the collective wisdom and decisions of the larger bodies. This model is the standard for Presbyterian and Reformed denominations.

A healthy polity is designed to keep leadership and laypeople alike accountable. A representative system, like the Presbyterian model, builds this accountability into its very structure by connecting local churches to regional and national bodies for oversight and support.

The Congregational Model: The Autonomous Local Church

Finally, the Congregational model champions the autonomy and independence of the local church. Here, the final authority for governance rests with the members of the congregation itself. Each local church is seen as a complete church, directly accountable to Christ and not subject to any higher human ecclesiastical authority.

In this "direct democracy" approach, the congregation typically votes on major decisions. These can include things like:

Calling or dismissing a pastor.

Approving the annual budget.

Electing deacons and other church officers.

Defining its own doctrinal statement.

While congregational churches are self-governing, they often choose to associate with other like-minded churches for fellowship, missions, and mutual support. However, these associations or conventions (like the Southern Baptist Convention) are usually voluntary and have no binding authority over a local church's decisions. A church can join or leave as its congregation sees fit. This is the model you’ll find in Baptist, the United Church of Christ, and most non-denominational churches.

To help clarify the key differences, here is a simple side-by-side look at the core features of each polity.

Comparison of Major Church Polity Models

Feature | Episcopal Polity | Presbyterian Polity | Congregational Polity |

|---|---|---|---|

Primary Authority | Bishops | Elected Elders (Presbyters) | The Congregation |

Structure | Hierarchical (Top-Down) | Representative (Layered Courts) | Autonomous (Bottom-Up) |

Clergy Appointment | Appointed by Bishops | Called by Congregation, Approved by Presbytery | Called and Hired by Congregation |

Local Church Autonomy | Limited; accountable to diocese | Partial; accountable to presbytery | High; self-governing |

Inter-Church Connection | Formal, through diocesan structure | Formal, through presbyteries & assemblies | Voluntary, through associations/conventions |

Example Denominations | Catholic, Anglican, Methodist | Presbyterian, Reformed | Baptist, UCC, Non-Denominational |

Each of these models offers a distinct vision for how the Body of Christ should organize itself to fulfill its mission.

Understanding these foundational structures is a critical first step for any church leader. For a deeper look into the theological and practical considerations behind these systems, you might be interested in our guide on choosing a church leadership structure.

The Biblical And Historical Roots Of Church Governance

The different ways we structure our churches didn't just appear out of thin air. They grew out of deep theological and historical soil, watered by centuries of biblical interpretation and real-world ministry challenges. To really get a handle on what is church polity, we have to dig into these roots to see where each model came from.

Every major approach—Episcopal, Presbyterian, and Congregational—is built on a distinct reading of the New Testament. If you talk to proponents of each, they’ll point you to specific scriptures to back up their view on leadership and authority. At the heart of it all are the roles and responsibilities we see in the early church.

Key Leadership Roles In The New Testament

The apostolic church had several leadership functions that still shape how we think about polity today. How a denomination interprets these roles often sets the blueprint for its entire structure.

Apostles: Figures like Peter and Paul carried a unique, foundational authority. Their main job was to plant churches and lay down authoritative doctrine. Some Episcopal models see the office of bishop as a direct continuation of this apostolic oversight.

Elders (Presbyters): The term presbuteros (elder) pops up all over the New Testament. These were the leaders tasked with teaching, shepherding, and governing local churches (Acts 20:17, Titus 1:5). This office is the absolute centerpiece of Presbyterian polity, where a council of elders holds the governing power.

Deacons: From the Greek diakonos (servant), deacons were appointed to manage the practical side of ministry—things like caring for widows and handling church resources (Acts 6:1-6). This freed up the elders to focus on prayer and teaching.

The big debates start when you ask how these roles relate to one another. For example, some scholars will argue that the terms for elder (presbuteros) and overseer/bishop (episkopos) were used interchangeably in the New Testament, referring to the same local church office (Titus 1:5-7). Others see them as distinct roles, which provides the biblical basis for a more hierarchical structure.

This is where you see the different models beginning to take shape.

This diagram really clarifies things, showing the top-down flow in an Episcopal system versus the more distributed power you find in Presbyterian and Congregational churches.

Pivotal Moments In Church History

Beyond biblical interpretation, major historical events also forged the governance structures we have today. After the apostles were gone, the early church gradually developed a more formal, hierarchical system. This led to the rise of bishops as central authorities in major cities.

This trend eventually culminated in the establishment of the papacy, cementing the Episcopal model in the Western church for over a thousand years. But that highly centralized structure ran into a massive challenge during the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century.

The Reformers, driven by a desire to get back to scriptural patterns, started questioning the entire established hierarchy. This theological earthquake threw the doors wide open for new ways of thinking about church governance, directly leading to the development of Presbyterian and Congregational polities.

John Calvin’s work in Geneva was hugely influential in crafting the representative, elder-led system that defines Presbyterianism. Around the same time, the Anabaptist movement pushed a more radical idea: the priesthood of all believers and the full autonomy of the local congregation. This laid the foundation for modern Congregationalism.

The ongoing debate over how to best apply scripture to church life is a fascinating one, touching on whether we should take a minimalist or maximalist approach to biblical commands. You can dive deeper into this by exploring the differences between biblical minimalists vs. maximalists.

What these historical movements show us is that church polity has never been static. It's a dynamic story of people wrestling with scripture and adapting to theological convictions, cultural pressures, and practical ministry needs. Each model represents a sincere attempt to faithfully organize the church, shaped by both the biblical text and the long, messy, and beautiful story of Christian history.

How Church Polity Functions In A Global Context

Church polity isn't some dusty blueprint you can just apply cookie-cutter style across the world. Think of it more like a living, breathing system that has to adapt to the cultural soil it's planted in. As the center of gravity for global Christianity makes a dramatic shift, understanding these adaptations is crucial to getting a real picture of church governance in the 21st century.

And this shift is no small thing. We’re talking about a profound realignment of the entire Christian world. For centuries, Christianity was centered in Europe and North America, but that's no longer the case. The majority of Christians today now live in the Global South, and that demographic reality is actively reshaping how churches organize, lead, and grow their ministries on a global scale.

The Rise Of The Global South

The numbers tell a stunning story. Recently, the Global South was home to 69% of the world's Christians, a figure projected to hit 78% by 2050. This isn't just a change in geography; it's a change in how the church is governed.

Take Africa, where Christianity saw an incredible annual growth rate of 2.59% between 2020 and 2025. This kind of explosive growth has a massive impact on polity. Churches have to train local leaders quickly, often leaning toward governance models that empower indigenous ministry from the ground up. You can dig deeper into this incredible trend by exploring the annual statistical table on world Christianity.

This demographic explosion creates the perfect environment for certain kinds of governance structures to take root and flourish. The pressing need for rapid leadership development and locally-owned, contextualized ministry makes decentralized models incredibly effective.

Why Decentralized Models Thrive

Across the fast-growing church landscapes of Africa, Asia, and Latin America, you'll find that congregational and presbyterian models are often the most adaptable. Their built-in emphasis on local autonomy and raising up indigenous leaders lines up perfectly with the needs of a church on the move.

They just make sense in these contexts. Consider a few of the advantages:

Speed and Agility: A congregational church can make decisions on the spot without needing a sign-off from a distant bishop or committee. This means they can jump on ministry opportunities as they arise in their own unique community.

Empowerment of Local Leaders: Presbyterian structures, with their focus on electing and training elders from right there in the community, create a sustainable leadership pipeline. This is a game-changer in regions where the church is growing faster than formal seminaries can keep up.

Contextualization: When local leaders are in charge, they can shape their church's worship, outreach, and ministry in ways that are culturally powerful and relevant. This avoids the classic pitfall of a one-size-fits-all approach being imposed from the outside.

The success of these models in the Global South drives home a key principle of healthy church governance: polity must serve the mission, not the other way around. A structure that works perfectly well in a stable, centuries-old parish in Europe might completely stifle the work of a vibrant, rapidly multiplying house church network in Southeast Asia.

Adaptations In Hierarchical Structures

This isn't to say that more hierarchical polities, like the episcopal model, aren't present or effective in the Global South. Far from it. But their success often hinges on their willingness to adapt. Many episcopal denominations in Africa and Asia have intentionally pushed certain aspects of their authority down to the local level, empowering dioceses and clergy on the ground.

These adaptations can look like:

Giving more autonomy to national or regional bishops.

Creating clear pathways for lay leaders to be developed and deployed.

Prioritizing the training and ordination of local clergy instead of relying on foreign missionaries.

In the end, what we see happening around the world shows us that church polity is not a rigid rulebook but a flexible tool. The future of church governance is being hammered out right now in the dynamic spiritual and cultural realities of the global church. It proves, once again, that the best structures are always the ones that best equip local believers to live out their faith right where God has planted them.

The Real-World Impact On Pastors And Congregations

So far, we’ve walked through polity as a theological idea. But what is church polity when the rubber meets the road? It’s far from an abstract blueprint; it’s the operating system that shapes the real, day-to-day experience of every pastor and church member. This is where theology gets practical, defining the processes for a church's most critical functions.

Think of it this way: polity answers the "who" and "how" behind every major church decision. Who hires the pastor? How does the budget get approved? Who owns the church building? How are doctrinal disputes handled? There’s no single right answer to these questions—each one is defined entirely by a church’s governance model.

Calling A Pastor

One of the clearest places you see polity in action is in the process of calling a new pastor. The experience is radically different from one system to the next.

Episcopal Model: In a top-down structure, a pastor (often called a priest or rector) is typically appointed by a bishop. The local congregation has little to no formal say in the matter. The bishop, who oversees a whole region or diocese, moves clergy around to fill vacancies, much like a district manager assigning a new store manager.

Congregational Model: Here, the power rests entirely with the local church. The members elect a search committee, which vets candidates. The congregation then votes to "call" a specific pastor. In essence, they hire the person who will lead them.

The presbyterian model often lands somewhere in the middle, involving a congregational vote that still requires final approval from a regional body of elders, the presbytery.

Owning Property And Managing Finances

Who holds the deed to the church building? This question might sound purely administrative, but it’s a crucial consequence of polity with huge legal and financial implications.

In an episcopal system, the local parish building is often legally owned by the larger diocese or national denomination. While this can provide stability, it also means the local church can't sell or even significantly modify its property without getting an outside approval.

On the other hand, in a congregational church, the property is owned by the local congregation itself. This gives them full control over their assets. The same goes for finances—congregational churches vote on their own budgets, whereas episcopal parishes often submit budgets for diocesan approval and pay a required portion of their income up to the larger denominational body.

Church polity provides the crucial framework for accountability. A healthy structure, whether congregational or connectional, is designed to prevent a focus on public image from overshadowing the core mission of humility, transparency, and faithfulness. It ensures checks and balances are in place for leadership and finances.

Handling Doctrine And Discipline

What happens when a pastor's teaching veers from established doctrine, or a member is involved in a public scandal? Church polity provides the roadmap for navigating these incredibly sensitive situations.

In presbyterian and episcopal systems, serious doctrinal disputes and disciplinary issues are often kicked up to a higher authority—a presbytery or a bishop. This external body has the power to investigate, make a ruling, and even remove a pastor if necessary. It provides an accountability mechanism that a purely autonomous church just doesn't have.

In a congregational church, discipline is handled internally. The process, usually outlined in the church’s bylaws, is carried out by the members or a group of elected elders. For those building a healthy church culture, you might find some great wisdom in these biblical reflections and practical tools for a vibrant church.

This focus on developing strong local leaders is a key part of global mission strategies. For example, the International Mission Board’s efforts have resulted in over 84,430 individuals being trained in church leadership roles worldwide. Of those, 20,655 were specifically trained as pastors or elders—roles absolutely essential to the presbyterian and congregational models that prioritize local governance. You can see the full scope of their work in these global church planting and leadership training statistics.

Ultimately, church polity is where theology gets its hands dirty. It turns abstract beliefs about authority, Scripture, and community into the concrete procedures that define the life, health, and mission of a local church.

Have Questions About Church Polity? Let's Talk.

As we move from the big ideas of church governance to how it all works on the ground, a lot of practical questions pop up. It’s one thing to know the theory, but seeing how it plays out in the day-to-day life of a church—well, that's where it really clicks. This section is all about tackling those common questions that pastors, leaders, and curious church members often ask.

Think of this as your go-to guide for clear, direct answers. We'll cut through the confusion and get straight to the real-world implications of these different ways of leading a church.

Which Form of Church Polity Is the Most Biblical?

This is the big one. It's probably the most asked—and most debated—question in the entire discussion. The honest answer? There is no universal consensus among faithful, Bible-believing Christians. Believers on all sides are sincere when they say their model is the one most faithful to the patterns we see in Scripture.

The disagreement really comes down to interpretation. Here’s a quick look at the core biblical argument for each view:

The Episcopal View: Supporters point to the unique authority given to apostles like Paul and Peter, who appointed and oversaw leaders in multiple churches (Titus 1:5). In their eyes, a modern bishop's role is a continuation of that apostolic function, providing crucial oversight and maintaining doctrinal unity across the wider church.

The Presbyterian View: This perspective highlights the consistent New Testament pattern of churches being led by a group of elders, or presbyters (Acts 14:23, Acts 20:17). They also look to the Jerusalem Council in Acts 15 as a biblical precedent for a representative, council-based government that connects different churches for important decisions.

The Congregational View: Proponents focus on passages that seem to give final authority to the local gathering of believers, especially in matters of church discipline (Matthew 18:17) and choosing leaders (Acts 6:3-5). They champion the autonomy of the local church as the fundamental unit, accountable directly to Christ.

Ultimately, the model a denomination lands on is rooted in its theological reading of these and other key passages. No single form has ever been universally accepted as the only biblical way.

Can a Church Actually Change Its Polity?

Yes, but it's rarely simple. A church can absolutely change its governance, but how hard it is—and what the consequences are—depends entirely on its current structure.

For an independent or congregational church, the decision is mostly internal. It usually means a formal process to amend the church’s constitution and bylaws, which almost always requires a congregational vote. Often, a supermajority (like a two-thirds or three-quarters vote) is needed to make it official. It's a big move, but the power to make that change stays within the local congregation.

For a denominational church, the stakes are much higher. Changing polity isn't just an internal adjustment; it's an act of separation. It means formally leaving the denomination—a move with profound legal, financial, and relational consequences.

A church in an episcopal or presbyterian system simply doesn't have the authority to change its polity on its own. Its governance is defined by the larger denominational body. To adopt a different model, the church would have to officially disaffiliate. This can get legally messy, particularly when it comes to who owns the church property, as it's often held in trust by the denomination. Just as importantly, it severs deep, long-standing relationships with other churches and leaders.

How Does Church Polity Affect Planting a New Church?

A church’s polity directly shapes how it plants new churches. The strategic, top-down approach of a hierarchical denomination looks completely different from the grassroots efforts you see in more autonomous church movements.

Here’s a snapshot of how the different models usually get it done:

Episcopal Model (Top-Down): Church planting is often a strategic, centrally planned effort. A bishop or a diocesan committee will identify a community, allocate the funds, and appoint a church planter or priest to get the new work started. This ensures the new church is aligned with the denomination's doctrine and mission from day one.

Presbyterian Model (Cooperative): This is typically a team effort led by the regional presbytery. The presbytery might commission a church planter, provide funding and oversight, and even form a core team from nearby member churches. The new church is "birthed" with a built-in network of accountability and support.

Congregational Model (Bottom-Up): Here, planting is often a more organic, grassroots endeavor. A single "mother church" might send out a pastor and a group of members to start a new congregation. Or, an independent planter might gather a launch team and seek support from a variety of like-minded churches and individuals. This approach allows for maximum flexibility and local ownership.

Each method is a direct reflection of its polity's core values—from the strategic unity of the episcopal system to the entrepreneurial spirit of the congregational world.

Ready to take your understanding of ministry leadership to the next level? At The Bible Seminary, we equip leaders with a deep, Bible-centered education that integrates theological knowledge with practical application. Explore our graduate programs and discover how you can be prepared for effective 21st-century ministry. Learn more about our degree offerings.

Comments